In democracies, economic currents often sway voters. With India’s economic rise, the state of national economy has come to occupy centre stage of political and public debates. Economic issues such as growth, unemployment, inflation, rural distress and so on figured prominently in political debates in the run up to the recently concluded general elections to the Lok Sabha. While the ruling party/alliance flaunted their impressive GDP numbers and new economic initiatives aimed at benefiting people, the Opposition bloc’s campaign remained focussed on unemployment, price rise and other forms of economic distress. Tapping into the downside of the economy, the Congress carefully crafted a package, called “Nyay” so as to be able to reach out to economically vulnerable sections.

For ordinary voters, complex macro-economic numbers may not mean much, but they have a fair sense of what they have gone through economically. Given this, it is people’s assessment of personal or household’s financial conditions rather than their perception about the performance of national economy that is expected to play an important role in shaping voting choice. The idea of “pocketbook” voting holds that those who feel economically secure or have experienced improvement in their financial wellbeing are more likely to vote for the candidates of the ruling regime. Conversely, individuals facing economic hardship, job loss or financial instability may seek to punish the incumbent.

Rural-urban divide

So, in the recently concluded parliamentary election, how did people feel about their personal/household economic/financial conditions? Did it influence their voting preference? If so, to what extent? The CSDS-Lokniti post-poll survey helps us answer these questions.

As per the survey findings, only four out 10 respondents felt that their personal/household financial conditions improved over the past five years. This means that economic condition of households of a great majority of people either remained unchanged or worsened. Interestingly, this number is about as great as it was in 2019. A closer look at the data indicates that a significant number of respondents actually experienced their economic conditions worsen. Compared with 2019, this number increased a bit. What this implies is that “achchhe din” could not expand its reach during the past five years (Table 1).

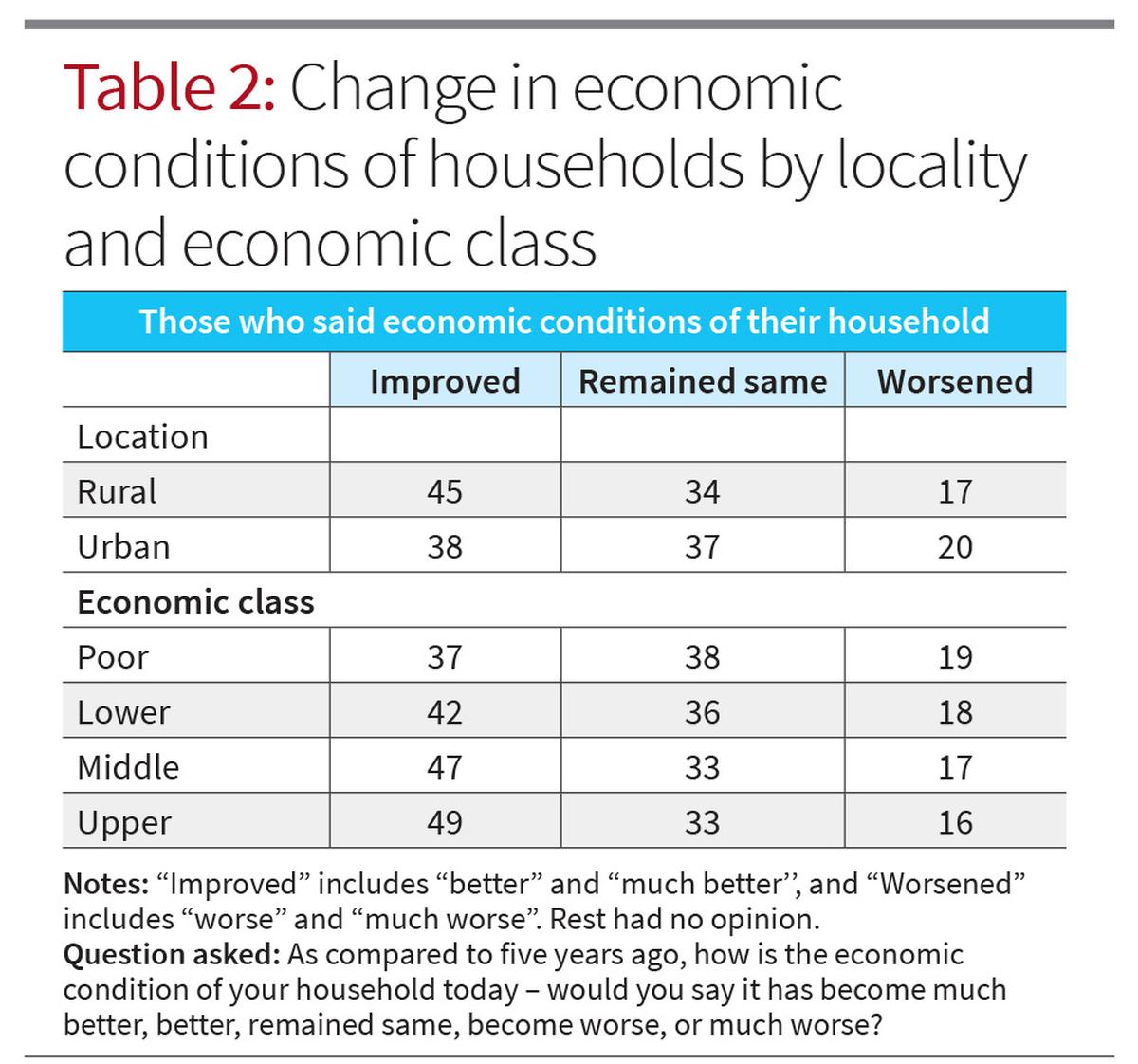

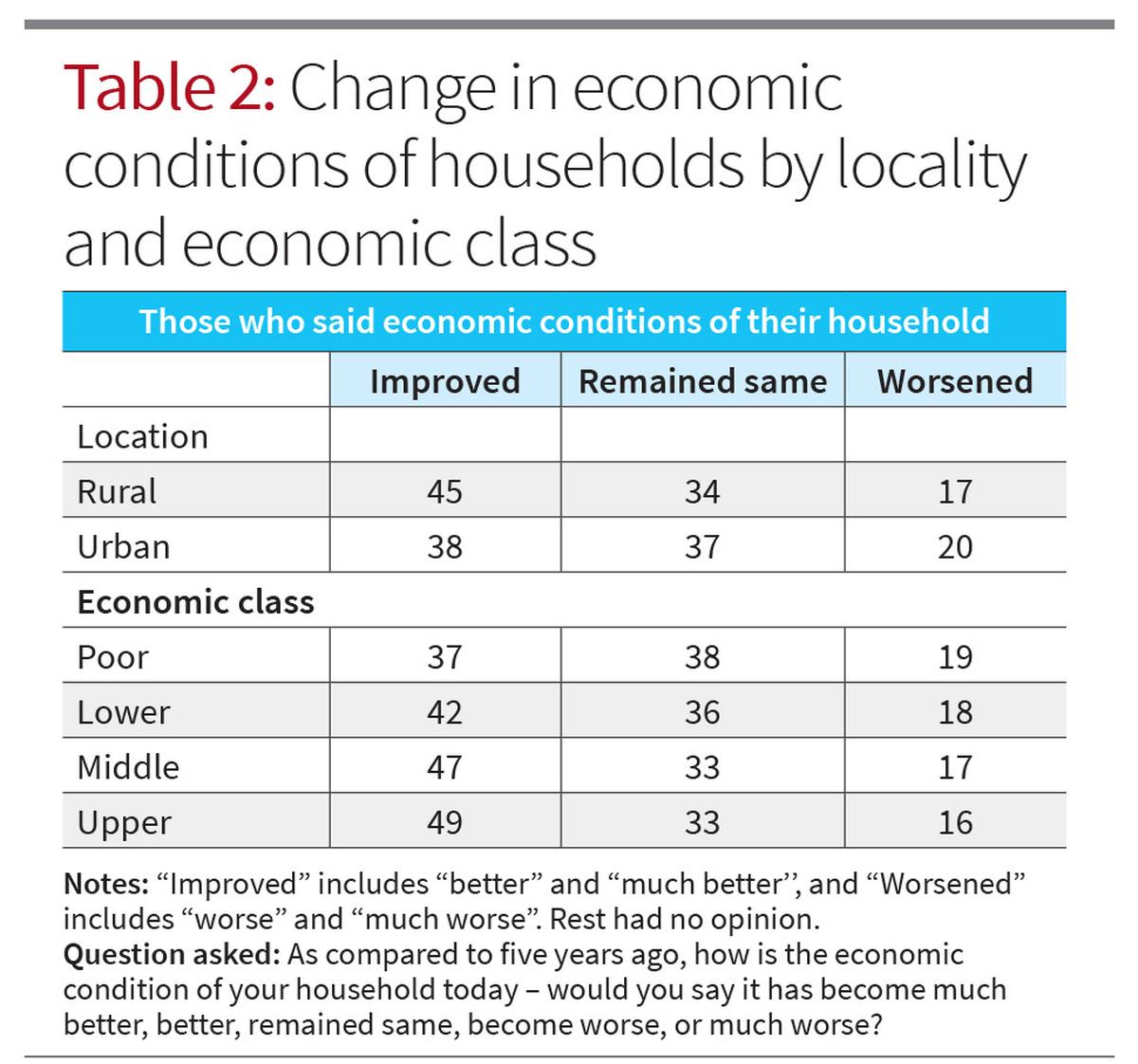

Who are those whose economic fortune improved or worsened? Economic processes are likely to affect sub-groups of voters differentially as their sources of livelihood and income markedly differ. An interesting pattern can be observed in rural and urban settings, the two spatially polarised contexts in terms of sources of livelihood and income. Data shows that more rural voters than their urban counterparts felt that their economic conditions improved. At the other end of the scale representing economic distress, the percentage of urban voters exceeded, though marginally, that of rural voters. The data also shows that the processes of economic development have impacted different economic classes differentially. While half of the rich respondents said that their economic conditions improved, the corresponding figure for the poor was as low as 37%. A larger fraction of the poor than others saw their economic fortunes decline (Table 2).

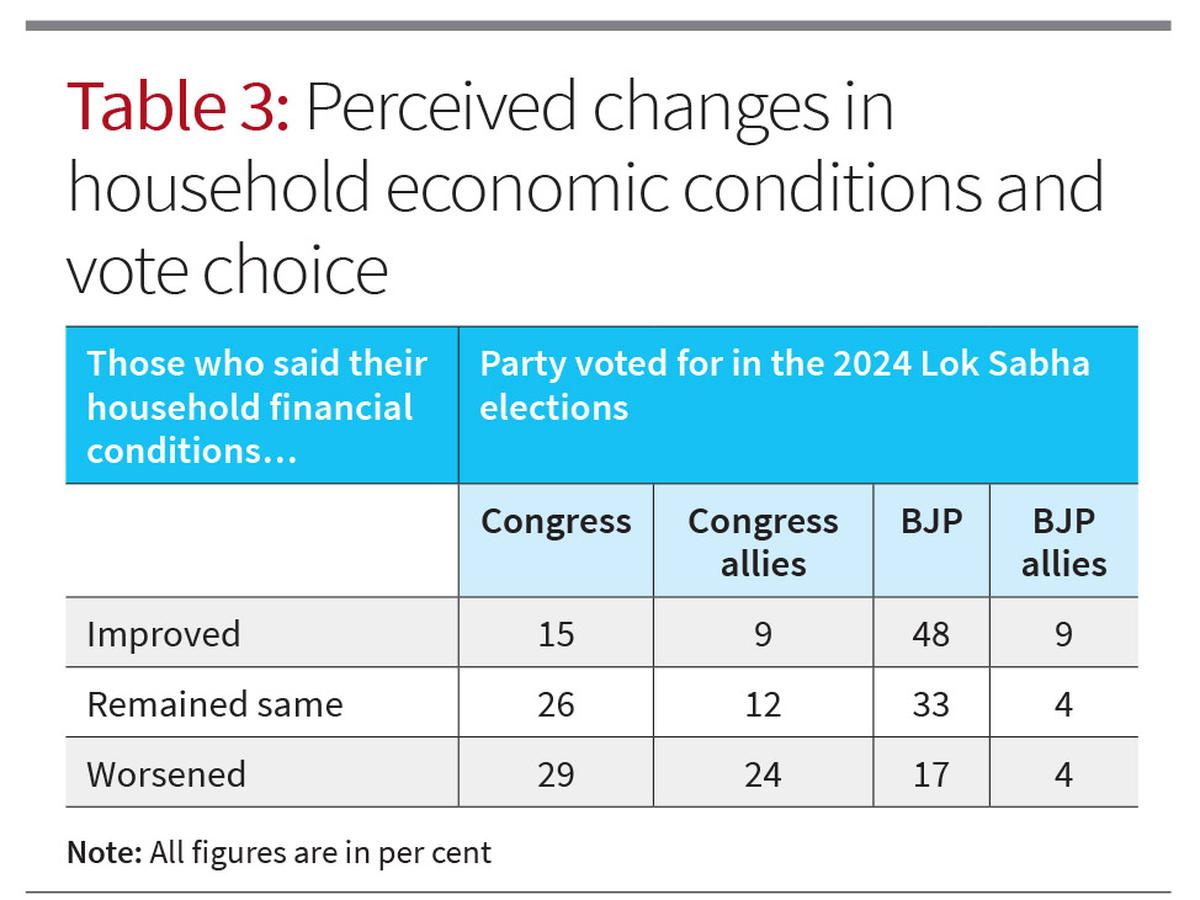

The way people perceived their economic conditions appear to have played an important role in shaping their political preferences. Data reveals that those whose economic conditions remained unchanged divided their votes almost equally between the ruling regime and the challenging party/alliance. However, those who experienced their economic conditions worsen had a clear preference for the Opposition camp. More than half of them would have voted for the Congress and its allies as against 23% for the BJP and its allies. Conversely, most of those whose economic conditions improved said they voted for the BJP-led NDA (Table 3).

A negative outlook

That key economic issues, such as personal economic well-being, mattered in the recently concluded elections is confirmed when we go back and take a look at other indicators as well. In the pre-poll survey held a couple of months back, three out of 10 respondents were of the view that the BJP-led NDA government worked for the benefits of the rich. About 15% of the respondents had held that there was no development at all during the past five years. Unsurprisingly, those who held a negative view of the ruling regime had expressed their intention to vote for the Congress and its allies (Table 4).

In sum, over the past five years, economic conditions of many people did not improve. A fairly large fraction of people actually saw their economic conditions worsen. Since this is only a preliminary bivariate result, it is difficult to say how much of a role personal economic conditions play in shaping final electoral outcomes. But it is quite clear that people’s assessment of their own economic conditions made a large difference in the voting choice.

Sanjeer Alam is Associate Professor at CSDS

#CSDSLokniti #postpoll #survey #Personal #financial #conditions #played #key #role #voting #choice